Harlan Ascending: Artist’s work grows with monument to Breonna Taylor, survey about equity in arts and culture sector

Her public art in front of Metro Hall includes poetry by Hannah Drake and the survey she has spearheaded poses serious questions about Louisville’s arts community

• If you enjoy articles about regional arts and creativity, share them and/or sign up.•

By Elizabeth Kramer

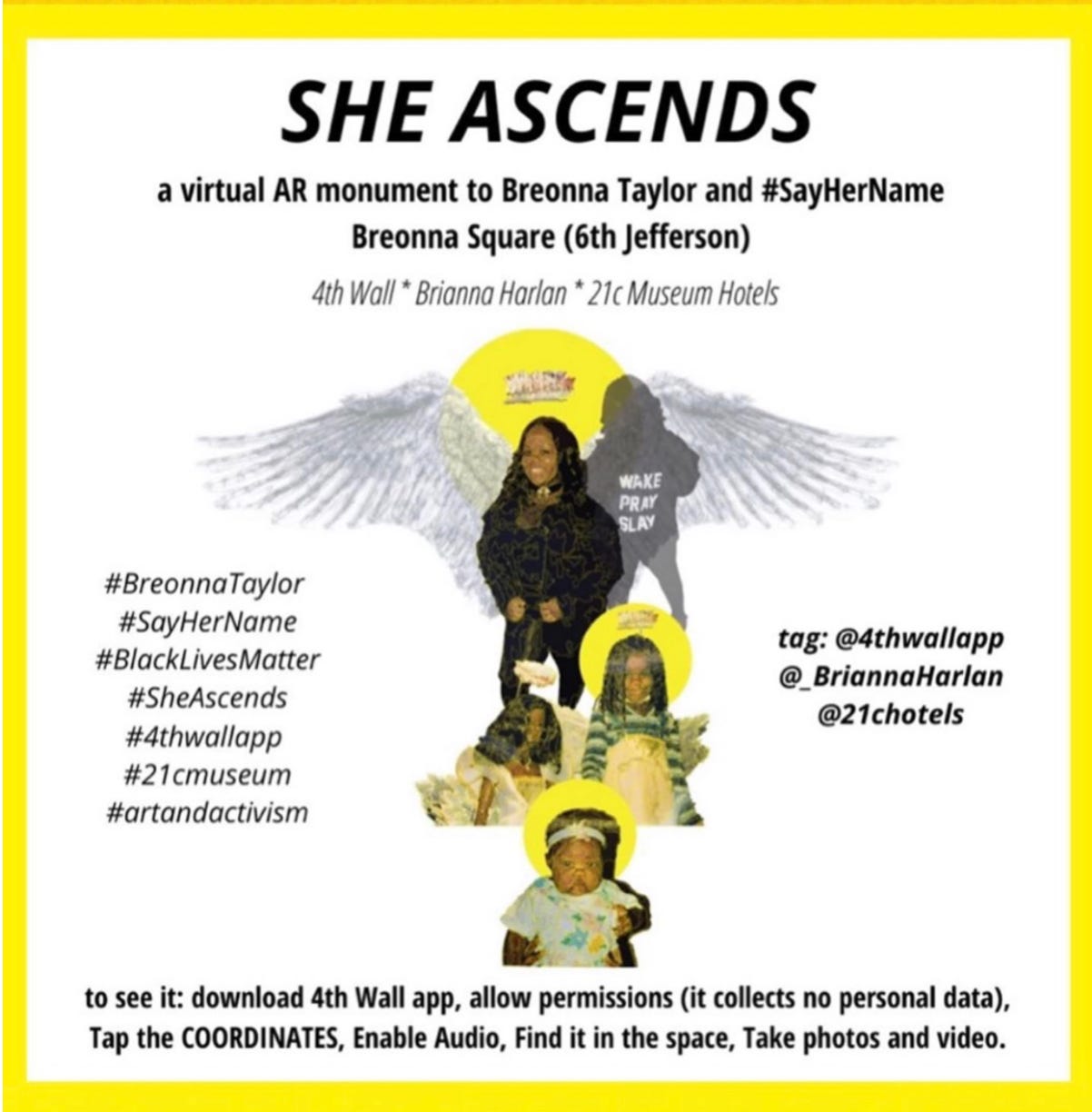

“It holds the space like a spirit,” said artist Brianna Harlan, who created “She Ascends,” a site-specific public art piece using augmented reality and geolocation.

Detail of Breonna Taylor in artist Brianna Harlan’s “She Ascends,” a site-specific artwork seen in augmented reality near Louisville Metro Hall.

Since late June, Harlan’s monument has hovered in front of Louisville Metro Hall over weeks of summer rains and heat and the ongoing protests against police violence in the name of Breonna Taylor, the Louisville woman who was killed when shot by police in March during a no-knock warrant, as well as that of George Floyd killed in May by police in Minneapolis. This is just one of several projects the Louisville artist has recently created and in the face of rising protests for justice for Taylor.

Using certain smartphones and the app 4th Wall, anyone can access “She Ascends” from the area across from Louisville Metro Hall and at the northern edges of Jefferson Square Park — renamed Breonna Taylor Park by many.

Other Arts Bureau Articles

• Louisville photographer’s work tells immigrant story in ‘PBS American Portrait’

• Speed Museum’s Curator Depart for Denver’s Contemporary Art Museum

• Reporters Covering Virtual Kentucky Governor's School for the Arts

After opening the app and pointing the phone to coordinated area, the vision appears hovering many feet over the ground and in front of the building. At certain angles, the monument can obscure artist and Civil War veteran Moses Jacob Ezekiel’s massive statue of Thomas Jefferson sited not far from the steps.

At the apex of Harlan’s piece, a collage of images of Breonna Taylor, mostly black-and-white images with one in color. That image depicts Taylor with wings. The others are of her as a child with halos. Below her, are throngs of women some with signs. They read “Say her name,” “Breonna Taylor,” “Justice for Breonna” and more.

To the far left and right, two pillars rise with images of two women’s faces whose identities are revealed through a poem, part of the artwork, by collaborator Hannah Drake.

Seconds after chants of “Say her name. Breonna,” those sounds of the soundtrack fade to Drake’s deep voice.

“If I close my eyes

I can see them.

Nancy Green

Alberta Jones

Breonna Taylor

And if I quiet my mind

I can hear them

Their voices carried on the wind…”

Drake repeats their names, inviting wider awareness of their stories as part of our collective history. In Harlan’s image, Green’s and Jones’s faces appear atop the columns.

“She Ascends” came about in the wake of the protests that erupted in Louisville on May 28 following release of recordings of 911 calls at the time of Taylor’s death. Just after that Los-Angeles-based artist Nancy Baker Cahill, 4th Wall’s founder and creative director, contacted 21c Museum Hotel Chief Curator and Museum Director Alice Gray Stites. Cahill was looking to use the 4th Wall platform for an artist’s work that honored Taylor and created discussion.

Cahill, who has family ties to Louisville, had met Stites in recent years. The artist said she founded 4th Wall to apply “augmented reality and geolocation to creating public art that engages issues and questions fearlessly.”

Video recording of “She Ascends” by Brianna Harlan, poetry by Hannah Drake, 2020. (Recording includes complete poem.) From Elizabeth Kramer using 4th Wall app.

Harlan said she wants “She Ascends” to help reflect on the injustices and violence Black women have faced for decades. That brought her to embrace the overarching idea of a monument to Breonna Taylor with the Say Her Name movement and work to honor and declare the names of other Black women who are often discounted.

“So often Black women are erased, forgotten and not given support,” said Harlan. “Black women aren’t taken seriously. We have to fight for women more.”

To mount the work, Cahill said Harlan worked with Stites in Louisville while she geo-located the work from more than 2,000 miles away.

“Alice showed up in front of Metro Hall with Brianna to observe and help situate the work and record the sound and document it,” Cahill said. “And it has lived in the world ever since.”

Directions to use 4th Wall app to see “She Ascends.” Courtesy Nancy Baker Cahill.

While documentation of the piece has circulated on social media platforms, Cahill contended the intended experience of this monument is seeing and hearing the artwork in downtown Louisville via the 4th Wall app.

“You’ll hear some chanting and then you’ll hear Hannah Drake’s beautiful, wise, rich voice ring out,” Harlan said of the audio that speaks of Taylor, Green and Jones. The latter two are significant figures in “She Ascends.”

Green, on Taylor’s left and known as the original “Aunt Jemima,” had her likeness and parts of her recipe used for years by the brand pancake syrup company. Green, born a slave and had lived in Mount Sterling, moved to Chicago after the Civil War. Her heirs filed an unsuccessful lawsuit claiming Green had not been fairly compensated and requested rights to revenues from sales of the brand.

“She wasn’t killed,” Harlan said, “but that’s a form of violence.”

The artist was referring to the appropriation of Green’s likeness, the corporate use of her and the product she had originated for its profit.

But Jones — who the first woman appointed city attorney in Jefferson County — was killed. Until this day, the identify of her murder(s) remains a mystery. On Aug. 5, 1965, Jones, then 34, was beaten and her body cast into the Ohio River. Despite some evidence, no one was ever charged.

Other Arts Bureau Articles

• Actor in video using the Bard's words illustrate outrage over Floyd's murder

• First YPAS choral teacher, leader in Louisville’s music community, dies

Stites said that Breonna Taylor’s image presented along with those of Green and Jones cover important historical ground.

“We need to unpack the past and the history lessons that didn’t get taught,” Stites said. “It’s what we need now, because if we don’t, we’ll never figure out how we got to this place.”

Figuring out this place is a tall order. But Harlan’s work is seeking to do just that and find justice. She had been living and studying in New York at Queens College for her Master of Fine Arts when the Covid-19 pandemic caused the spring’s business and school closures. When cases in the pandemic surged followed by protests against Taylor’s killing and racial discrimination, Harlan commited herself to working in her hometown and taking part in the struggle to find justice for Taylor.

She also brought with her a breadth of experience in the art scene coupled with community service. While she had practiced a bit of her artmaking after graduating from Hanover College in 2015 and worked in education at KMAC, her ambitions grew after she participated in the Community Foundation of Louisville’s Hadley Creatives program (funded by the George and Mary Alice Hadley Endowment Fund).

Artist Brianna Harlan in a video she created on Instragram created in which she gives results of a survey she spearheaded, “Louisville Arts Scene: Injustices and Inequalities.” Courtesy Instagram.

Community work bookended her time at KMAC with a position at Louisville Grows as an AmeriCorps’ VISTA volunteer and another as a liaison working with community groups through the Center for Neighborhoods. She also reentered the museum world working at the Speed Art Museum as a community outreach coordinator before heading to graduate school.

After beginning her studies in New York, she started working for City University of New York Colleges with an equity educational program called Center for Ethnic, Racial, and Religious Understanding or CERRU. The area in which Harlan works with the center focuses on working with the university community on several issues including understanding bias and fostering mediation and dialogue among diverse groups.

Being in Louisville this summer has not led her to abandon her artmaking. It helped lead to recent artwork, such as her “Castleman Statue Cleansing Ritual,” a public art event that involved the burning of herbs to cleanse the spot where the statue of John Breckinridge Castleman once stood. On June 8, the city removed it from the Cherokee Triangle neighborhood following years of debate about Castleman’s legacy and involvement in the Civil War.

Other Arts Bureau Articles

• Artists working in Kentucky among 2020 Guggenheim Fellows

• StageOne Family Theatre names Andrew Harris new producing artistic director

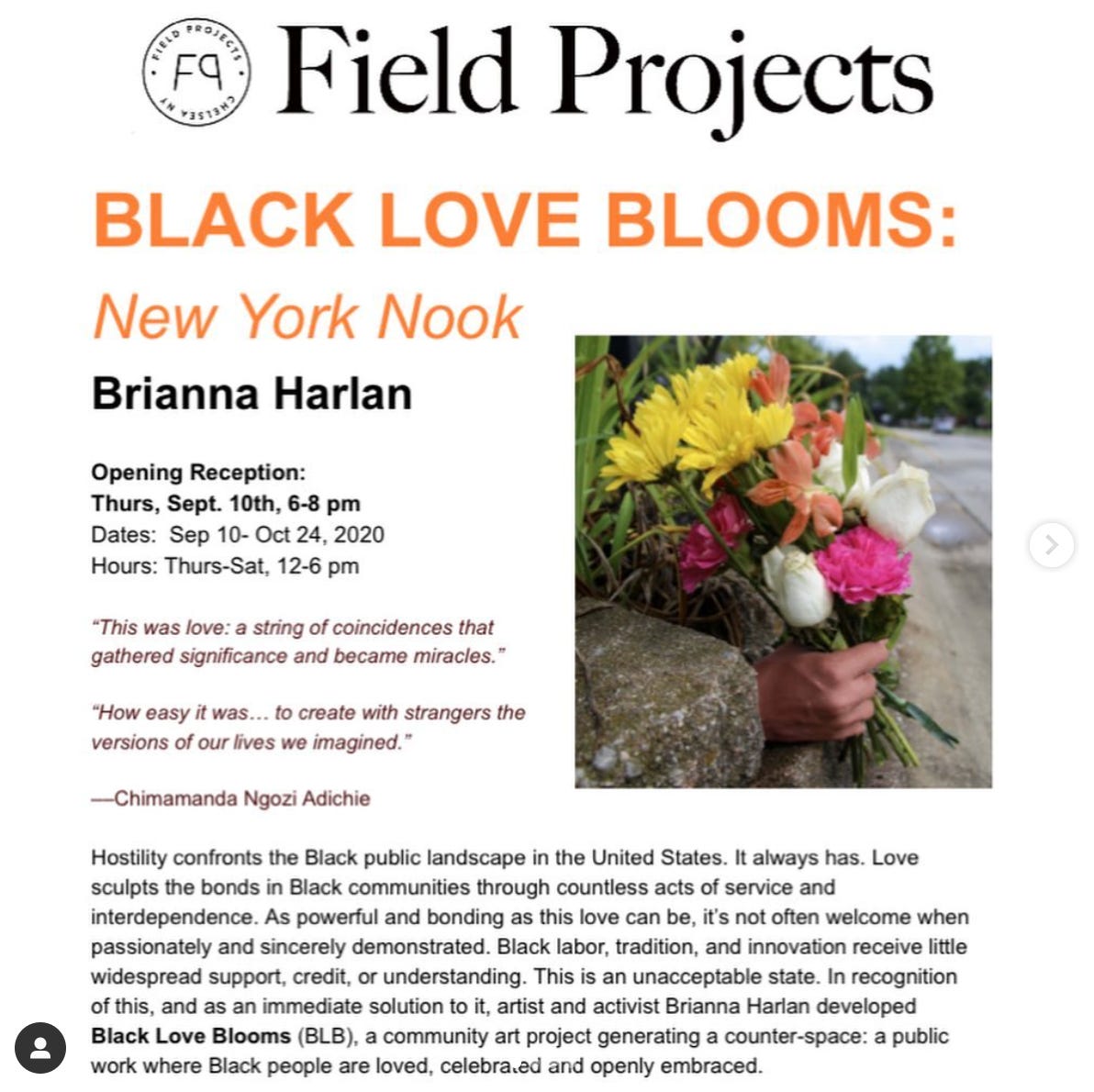

This past Juneteenth, Harlan continued “Black Love Blooms,” a performative work she started in New York last year and has performed in Louisville and four other cities. The art work or practice entails the offering of flowers to Black people in a gesture of love, joy and support. The work ventures to contest the often-reported narrative of Black people neglecting their communities and each other and continues with an opening in September with the artists’ work in “Black Love Blooms: New York Nook” at Field Projects, a gallery in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood marking Harlan’s first New York solo show.

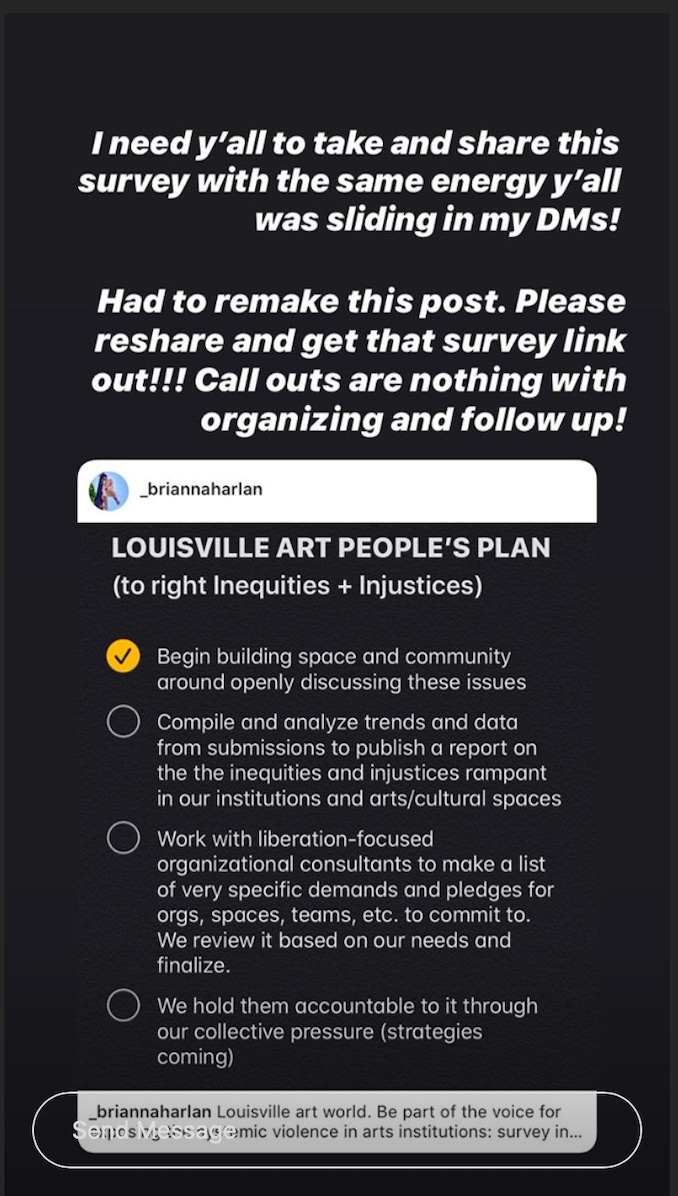

But Harlan launched another project here after familiar stories of neglect began to occupy her thoughts and prompted her to apply her community organizing skills here. The stories came from people in the local arts community she had reconnected with in June. Harlan said they spoke about the dearth of Black people employed at many local arts organizations, frequent lack of inclusion for Black artists and other creatives in area events, and even mistreatment. She said she has experienced some of this first hand, being one of the few Black persons working in past jobs at KMAC Museum and the Speed Art Museum.

A post Brianna Harlan made to Instgram about her upcoming exhibit in New York. Courtesy Instagram.

First, Harlan posted on social media about these issues and experiences faced by her and others.

“I had written up my slides and story,” she said. “I didn’t expect as many responses as it got but it snowballed.”

Harlan then decided she needed to capture the experiences — those accounts of pay disparities, tokenism and other scenarios of exploitation. So she created and put out “Louisville Arts Scene: Injustices and Inequalities,” a survey. (She is working with someone she keeps anonymous who works in the social sciences to codify the results.)

“We need to have this conversation,” she said. “Everybody is in the position now where they have to listen or are open to listening.”

On July 24, Harlan announced the survey’s findings in a talk she gave at the monthly speaking series Creative Mornings: of the survey’s 250 participants, 90% marked did not see diversity represented at the area’s art openings and other events; 95.5% did not see the black creative community fairly represented at commercial and career advancing events; and upward of 83% agreed that sexism, racism and tokenism is common in the arts and culture scene.

On Aug. 3, Harlan posted a video update on Instagram saying she and others are plowing through the information collected to produce qualitative analysis of injustice and inequity in the Louisville arts and culture scene. The goal is to create what she is calling the Louisville Art People’s Plan.

“We’re trying our best to make sure that it is everything that it needs to be and that we’re really taking our time with submissions since people really took the time to share their truth and their experiences,” she said.

Harlan gave no timeline, just upcoming goals that include a Zoom meeting that will include demands of the arts and cultural community and then meetings with individual organizations.

“This is what I’ve been trained in, so I’m doing what I know,” she said about this process in an interview.

This grassroots work echoes that of her grandmother, Mattie Jones, a renowned activist in Louisville’s civil rights movement who worked alongside the late Rev. Louis Coleman and has a place in the Kentucky Civil Rights Hall of Fame.

An announcement artist Brianna Harlan posted on Instagram about the the survey she launched in July. Courtesy Instagram.

Just before Taylor’s death and the pandemic shut down of most public events in March, Harlan’s artwork “You Sang Off Key” was part of an exhibit called “Ballot Box.” The work drew on Harlan’s grandmother’s experience in Mississippi of being tasked with singing the national anthem when she tried to vote only to be told she had failed and turned away.

The exhibit was held in Louisville Metro Hall — the same building just above where Harlan’s “She Ascends” now hovers with Breonna Taylor’s image made visible via the 4th Wall app.

In talking about the monument, Harlan focuses on Taylor.

“She’s a guardian angel,” Harlan said. “a guardian spirit over the site where people are protesting right in front of Metro Hall and where there has been a struggle for justice for her and for many people.”

Through the many facets of her own work, Harlan is gathering her own energy and creativity to take that struggle throughout this city.

Elizabeth Kramer, a multimedia journalist who has worked for newspapers and public radio, was a leading voice on the arts as the fine arts reporter at Louisville’s Courier Journal from 2010 to 2017. Her work has aired on National Public Radio and appeared in national publications. Never miss an update.